Everyone is talking about Iceland. That island in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean with Björk, an unassumingly victorious football team, and those hard-to-pronounce volcanoes. Its convenient location between Europe and North America has been taken advantage of on a higher scale in the past few years, and with Icelandair offering up to seven days of stopover time for free, why wouldn’t you go and see what all the fuss is about?

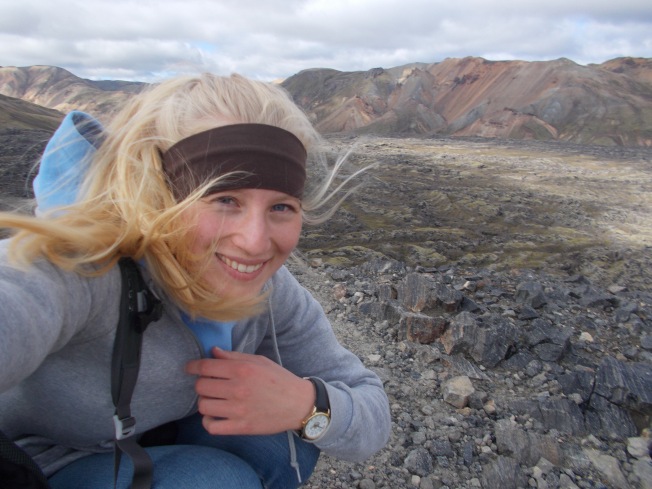

I first visited Iceland in August 2013. It was becoming more popular at that time but still had a minimalist feel to it that made me warm to it. I sensed that things would be different when I returned for a quick stop in December 2016 en route to Canada.

Some things remained the same. The FlyBus from Keflavík airport to Reykjavík still played the same man’s slow, soothing voice to welcome passengers. As we passed the same barren lands and swathes of lava fields, I still got flashbacks to medieval times, imagining Viking soldiers in battle. But as we entered the surrounding towns and suburbs of the city, I noticed more apartment buildings than before. Had they always been here and I simply hadn’t noticed? Maybe the sparkling Christmas lights just made them stand out more? No, there were definitely more. The place looked more developed and modern.

My friend picked me up from the BSÍ terminal and confirmed the development that had been taking place in and around the city. She asked if I had any plans for my two and a half days in Iceland. I realised I hadn’t given it too much thought; my main goal was to see the Northern Lights. But I also thought it would be nice to go to a geothermal pool, since I had chickened out of going to one on my last visit due to shyness about the nudity element of pre-bathing showering. I had always regretted what had later seemed like a pathetic reason not to go. My friend suggested we go inland to a geothermal pool to that was smaller, less commercial and more natural than the popular Blue Lagoon, a place I briefly stopped by at on my last visit and didn’t enjoy. She had also never been and so it seemed like a great idea.

After waiting for snow storms to pass the next morning, we set off. There are no signs indicating where the pool is. Once we arrived however, we were surprised by the number of cars parked up. I was expecting a very rustic set up with mostly native customers, but reception was bustling with a variety of nationalities. I paid 2500ISK for the ticket and followed my host to the changing rooms.

“So, we have to shower completely naked here, don’t we?” I asked, feeling the butterflies from three years ago begin to flutter back into my stomach. My friend nodded with a smile. I took a deep breath and undressed, looking straight ahead as I walked towards the shower. It was as if I thought this would stop people looking at me, but I soon realised that nobody was going to look at me anyway. Showering naked in public was so much less of an issue than I had previously let myself believe. Good on Icelanders for their fearlessness and their motive to protect their natural pools. Later on, I would even find myself shooting disapproving glares at the back of a bunch of Brits who I noticed proceed towards the pool having showered in their swimsuits. We are definitely a prude nation when it comes to public nudity (which seems ironic given that we have a fame-obsessed culture that promotes sex through various mediums).

The pool was very relaxing. There was even something refreshing about having your face pelted with hail stones from above whilst your body remained submerged in warm water. However it wasn’t as quiet as I’d hoped. Perhaps selfishly, I’d expected fewer people. As more loud groups entered the water and the drinking increased, the experience became more distracting than relaxing and we got out. Before arriving, I had already decided that I wouldn’t write a blog post about the place, in order to preserve its secrecy. I’ve since realised that the pool’s name of the Secret Lagoon has become an appealing marketing tool, and there is actually no secret to hide anymore.

The next morning over breakfast, my friend read a newspaper article which highlighted the growing problem of tourists feeding horses in the wild. These animals are not used to eating sugar or bread, and the treats were actually causing more harm than good, with more horses suffering from digestive problems without access to medical help. If you are reading this and planning to road trip through Iceland, please do not feed the horses or try to bribe them with food to come closer. They are self-sufficient animals and will not starve without your treats, nor suffer without your petting.

Another article discussed the rising number of car accidents on roundabouts as foreign visitors do not adopt Iceland’s road rules. On a roundabout, those in the inner lane have right of way to exit. I know – seems bonkers – but we should respect another country’s rules nonetheless. Another article reported that Keflavík airport had seen a record 6 million people enter its doors in 2016, a 25% increase from 2015. There are 323,000 inhabitants of Iceland.

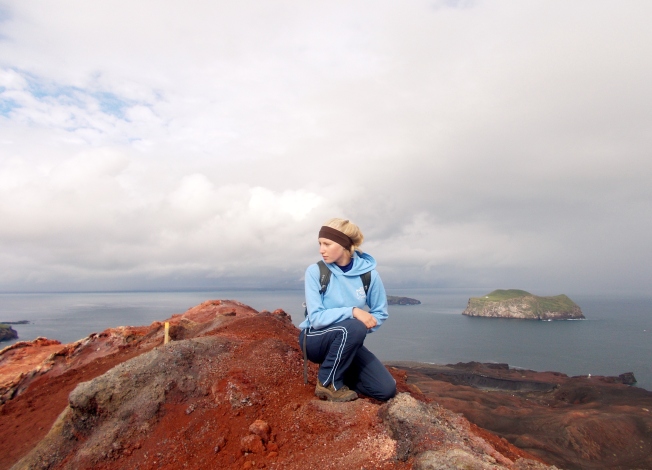

That day, my friend took me on a rainy tour of the Reykjanes Peninsula in the southwest of the country. Lava fields smother the land where you can find the Bridge Between Continents – a fissure in the ground where the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates meet and diverge. The gap grows by 2 cm every year. Further on is Gunnuhver, the steam vents and mud pools of which are named after a female ghost whose shouting is supposedly symbolised by the eruption of the geyser. Reading her story reminded me of the mythologies I learned on my last visit – cultural traditions that helped make Iceland unique in more ways than its geology and landscape. Ferocious waves battered the cliffs as we drove further on. I read about a bird called the Great Auk, the last colony of which lived on a small island called Eldey off the coast of Iceland, before becoming extinct in 1844. Similarly looking to the penguin, it was flightless and stood no chance against human hunters.

In the town of Grindevík, we ate lobster soup in a small cafe decorated with ship memorabilia and an old piano. A group of Americans got up to leave shortly after we arrived, thanking the owner. The ditsy 20-something daughter then said to her mother, “How do you say ‘thank you’?” The mother had no answer. My friend grinned at me and I felt like dunking my face in my soup. A perfect example of one of the bad travel habits I wish I could see less of. Maybe I think too much, but I find that there’s something so rude about coming to a foreign country and not even bothering to learn one simple word (“takk”). Some might argue that paying money for a travel experience represents enough ‘giving’ and justifies the ‘taking’, but I think this outlook promotes an imperial-esque sense of self-entitlement and disrespect for local culture.

On my final morning, we took my friend’s dog for a quiet walk around a frozen lake. The only others we saw were a runner, another walker, and a party of horse riders. I got the impression this was one of a decreasing number of places locals could come to where they wouldn’t find many tourists…at least in the early hours of the morning. In downtown Reykjavík later on, my friend pointed out the construction of new hotels. It’s a contentious issue, the threat that hotels and other tourist accommodation options like Airbnb pose to long-term rental space for locals. You get the sense that some natives feel they are prioritised below tourists when it comes to urban planning.

Overall, my short return to Reykjavík was enough to illustrate the increased popularity of Iceland as a tourist destination since I last visited. (Me ahead of a trend? Wow.) I’m not saying it’s bad that Iceland has become more popular. Afterall, as my friend acknowledged, tourism is good for the country’s economy. But my brief visit also illustrated the potential problems Iceland faces from its popularity growth. Its authenticity makes it popular and yet I worry that this is under threat from pressure to meet the expectations of tourists who come from more consumerist, materialistic, and fast-paced countries. I fear it’s in danger of becoming exploited at the expense of its culture, citizens and landscape.

I think of the slowly widening rift between the tectonic plates and relate it to what seems like a gradual tourist-takeover of Iceland. I think of the geographical mythologies and wonder if they’ll ever become regarded as archaic and unmarketable. I think of the Great Auk being hunted to extinction because of human greed. You’ll find ignorant and inconsiderate behaviour from tourists in any country, but for some reason I get defensive when Iceland is the victim. It’s perhaps because I have experienced the country from the perspective of both a tourist and local. I know how hard living in Iceland can be for Icelanders, and am able to see how large volumes of tourism can contribute to this. Are there any “secret” places anymore? Apart from their homes, where can native Icelanders go where they are free from tourist-oriented advertisements, expensive cuisine, English-speaking “banter” and complaints about WiFi?

I didn’t see the Northern Lights as hoped during my brief stay, as skies were too cloudy. Although it was a shame not to witness something I’d been hoping for, I took comfort knowing that there remains something in Iceland that can never be influenced and caused by tourist demands and actions. A natural phenomenon that doesn’t give a hoot about how much people want to see it and how much money they have to offer.

Please visit Iceland, just don’t plunder it. Support the economy, just don’t govern it. Embrace the culture, just don’t squash it. Take many a photo of the nature, just don’t leave a mark on it.