One day as I went to leave my flat for a class during my second year of univesity, I went to spritz myself with some body spray, but nothing came out of the can. I shook it and pressed down harder on the releaser, but there was no sound of jolting liquid from inside; instead all I heard was a pathetic gasp of empty air. I unwillingly put the can back down, feeling a brief sense of glum. I had other deodorants and perfumes that I could use, but for some reason I still left feeling incomplete, as if I’d lost something.

Then a week later, my watch stopped working. At face value it’s not a particularly special watch of huge monetary worth – a black leather strap wearing away on the inside, its face with its lightly scratched surface surrounded by a golden rim smudged with fingerprints. Most people wouldn’t look twice at it, probably thinking it was a piece of junk. I didn’t even wear it in or outside the flat and hardly even used it to check the time, using items of technology such as my phone or laptop instead. And yet just having it around provided a sense of comfort, so that when I no longer heard its faint clicking and instead saw its hand twitching weakly, I felt a pang inside.

Why was it that I was so moved by these items losing their function? They seemed so insignificant. Financially they were of minute value. But their sentimental worth was huge.

I found the watch when I was in Australia, having met up with my sister for a road trip up the East Coast. We spent a night in a hostel in Byron Bay, where it was attached to the base of the bed above me. For some reason it really caught my interest, and I lay in bed just looking at it. I knew that it had probably been left there unintentionally, and that I should probably give it into reception in case someone returned for it. But another part of me wondered if it had been left there on purpose, as a ‘gift’ from one traveller to another. In the end, I took it with me. At first I felt quite bad for proclaiming it as my own – had I not technically just stolen something? But I later came to believe that I really had been meant to take it.

A few months later I was in Canada, on my first proper solo backpacking trip, with the watch strapped securely to my left wrist. On my first full day I went to see Niagara Falls. As a girl used to the countryside over the city, my arrival in Toronto had been pretty overwhelming and I was still not quite at ease with the whole ‘going-it-alone’ process. On the bus back, we passed a sprawling lawn decorated with a flowerbed cultivated into the words ‘School of Horticulture’. The words rang a bell but I wasn’t sure why. I absent-mindedly looked at ‘my’ watch to check the time, only to fully comprehend what the tiny writing on its face said: ‘Niagara Parks Commission – School of Horticulture’.

Excitement shot up inside me. It was a bit like the feeling you get when you finally crack the answer to a difficult question – it’s often at a time when you aren’t really thinking about it and instead the answer suddenly comes to you just like that, causing a feeling of accomplishment and disbelief. Despite the seemingly obvious word ‘Niagara’ (and image of a maple leaf), never before had I associated the watch with Canada. The overly-imaginative girl inside me began to believe it was a sign; the watch had indeed been left for me and I’d been destined to come here all along, to continue the journey that its previous owner had begun, and perhaps other owners before him/her. I didn’t want to accept the high possibility that it had just been pure coincidence. Before arriving I’d had doubts about my reasoning and ability to travel alone, but now my trip seemed to have a greater purpose, and any doubts were washed away, all thanks to a boring old watch.

The story behind the body spray isn’t as memorable. I bought it in a ‘Canada Drugs’ store a few weeks into the trip, simply because (I was increasingly conscious of my lack of showering and) it was cheap, to the extent in fact that it was almost tacky (‘Mystical – Our Version of Fantasy Britney Spears’) But it had a nice smell – like candyfloss. Whenever its fragrance filled the air after returning home, the fumes would transform my mind back to little moments from the trip where the aroma had been present: moments of joy and excitement; friendship and romance; sadness and frustration. It seems pretty fascinating, when you think about it, how powerful this sense can be for stimulating certain emotions.

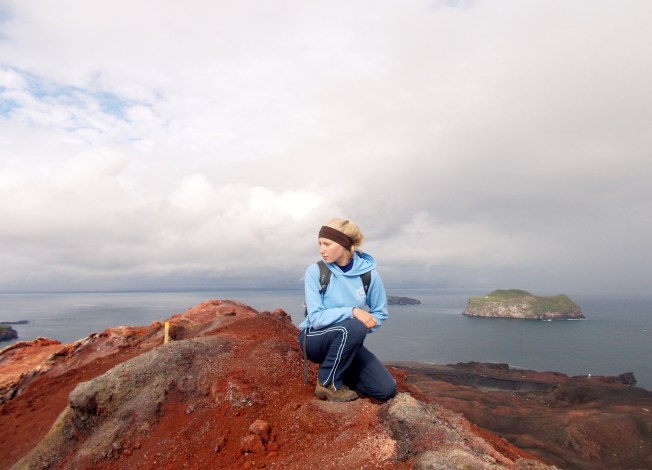

From that trip onwards, the watch went on to become for me that special ‘thing’ that many people have and always treasure. It’s normally a cuddly toy that one can snuggle with for comfort or childhood nostalgia, a special stone that acts as someone’s lucky charm, a poem written by a loved one, or a piece of jewellery passed down through a family generation. But for me, it was a plain old watch – an item that only I as the owner could understand the personal significance of. The watch is often a feature in my travel photos, yet few will probably pay much attention to it, viewing it as having only a practical purpose. But it’s the personal experiences surrounding such random objects that make them so special and worth holding onto. They are a gateway to a meadow of memories.

It’s fair to say I can get a bit OCD about collecting souvenirs though. And by ‘souvenirs’ I don’t mean t-shirts or mugs bought from a shop at the airport, baring the country’s flag. When I returned home from Canada and reluctantly began unpacking, jumbled together in a plastic bag at the bottom of my bag was a bunch of travel tickets and scrunched-up receipts from certain Canadian shops; dog-eared tour brochures and ripped maps; scraps of paper on which I’d written notes of bus times or the name of a musician I’d heard; pebbles and flattened grass stalks; wrappers and labels from confectionary and drinks specific to that country. I knew it looked slightly OTT, and yet when I discovered later that one of the chocolate wrappers had been put in my bin (mother!) I rushed over in horror to remove it and place it delicately in a box that would later become devoted to travel souvenirs, as if returning an abandoned baby to its cot. Some might say this is the behaviour of a person with worryingly excellent stalking potential, but fresh from the trip I was just so desperate to cling onto every memory. Each random item took me back to experiences that I wanted to remember, either because they made me feel proud, happy, amused or curious.

Now I’m a little more relaxed when it comes to my souvenir-hoarding, by that meaning I’ve removed the presence of food-related memoirs (mainly because it just makes you crave something you can’t access in your own country). But I stand by the other assortments, curious as to whether, looking through them again in 40 years, they would spark a recollection of some personal event or emotion. I think on the whole, the weirder one’s collection of souvenirs, the more interesting stories they have to tell. It’s fair enough for someone to return home with a load of expensive items from Duty Free, or famous gifts from the Tourist Office shop, but it’s unlikely that these items will provide a special memory of a place. Furthermore, everyone can take a photo of one famous amazing site, but photographs alone can’t necessarily remind one of a unique memory related to it.

You might be wondering how I managed to keep a 75ml can of body spray going for two and a half years. I think that sub-consciously I was conserving it, not wanting to finish it because that would mean the ending of a tie to certain memories. And so when there was nothing left in that can it was briefly a sad moment, because it appeared to reflect the loss of a link. Likewise, seeing the watch sit silent seemed to signal the end of something, as if a chapter had been closed. Canada was the story I’d been forced to stop reading early because an upcoming degree required other commitments, and I was reluctant to forget the storyline and the characters completely. The spritzes of spray in the months after acted as a reminder; snippets from the plot I’d immersed myself in. Whilst I had fantastic stories to tell from countries elsewhere afterwards, Canada continued to top the list for the book I found hardest to put down. Now that the scent would no longer hover through the air and the watch no longer tick along, it was as if there were no more words to read – it was time to accept that, two and a half years on, the trip was officially in the past and no longer a new, glossy book on my memory shelf.

Of course, this doesn’t at all mean that the memories are gone forever. But when one places so much sentimental value on an object, it is easy to feel that a connection to an experience has been weakened in some way. Some people might think trying to maintain strong attachments to travel memories through the form of objects is lame. But what’s wrong with trying to retain a nostalgic association, if the experience really meant something to you? I don’t think people should feel embarrassed about holding onto certain mementoes from a trip because they might seem pointless, unfashionable or weird to others. At the end of the day, it was your personal experience and only you can understand the sentimental worth of something. Hold on to anything that made you feel anything, because then in later years you at least give yourself a chance to reflect and remember.

***

Relevant links: Souvenir Finder